Art as a Curative Tool

By Pip Burrows

Date

April 11, 2017Art, in its many forms, has been an intrinsic part of human culture dating back almost 100,000 years. It embodies a momentary way of life at a given point, often with the capacity to evoke particular emotional responses. When talking about art, it is important to first clarify the bounds within which this term applies. In a society engulfed by imagery and perpetual visual stimulus, the aesthetic qualities of art are largely thought of as the objective outcome. Its essence being reduced to a static, flat image; as Juhani Pallasmaa observes ‘the dominance of the eye and the suppression of the other senses tend to push us into detachment, isolation and exteriority’. Art can be more aptly described as a poetic language that has the capacity to engage the imagination and connect directly to our experiences and sense of self. It is a medium that encompasses a vast range of disciplines not limited to an aesthetic visual image, but rather anything that seeks to engage us on an emotional level, in whatever form that may take. In its purist sense, art has the capacity to be an integrated element within a designed space and not limited to a visual affix.

Architecture has been, and arguably still is, inclusive within the subject of art. It is the means through which the spatial narrative is brought down to a human scale, enabling the individual to connect with the environment surrounding them; opening up the opportunity to curate a particular range of emotional responses towards the spaces being designed. It is worth noting that both negative and positive responses are possible, and goes without saying that within curative environments the latter is naturally preferable. This leads to the question: How can a positive response be triggered?

One of the predominant, but not singular, characteristics to feature in creating positive outcomes and enhancing wellbeing is the natural environment. The idea “that contact with nature is somehow good or beneficial for people is an old and widespread notion”. For many years, there have been studies and discussions that have sought to understand this affiliation towards the natural environment, and it is now clear as to the positive impacts such contact can have on enhancing human wellbeing. Of particular note are the research and observations by Roger S. Ulrich, Edward O. Wilson, Stephen R. Kellert, Dorion Sagan and Lynn Margulis, to name a few. The various texts build a strong case for the inclusion of biophilic design principles when considering curative environments. With such strong arguments being presented, the application of these biophilic design principles within the remits of art are likely to result in inherent positive affiliations.

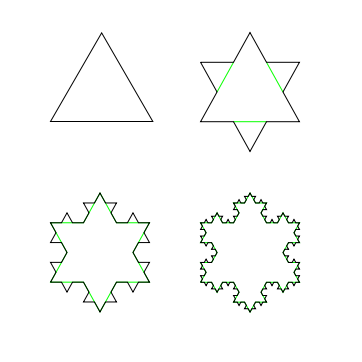

To illustrate the range of possibilities this reveals, natural themes are not only limited to the often stereotypical depictions of nature. Interestingly, they can be broken down into its core elements offering a certain degree of abstraction, whilst still inducing a positive emotional response. One such example is the use of fractals; patterns which have a self-similar configuration in varying scales (neatly illustrated with the Koch Snowflake in Image 1). They are found throughout nature in many forms and visual perception studies have already revealed a human preference for fractal landscapes and structures, which have also been shown to reduce stress, like in images 2 and 3.

Image 1 – Example of one of the earliest fractal curves.

Image 2 – Fractal broccoli

Image 3 – Staccato lightening – by Griffinstorm – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

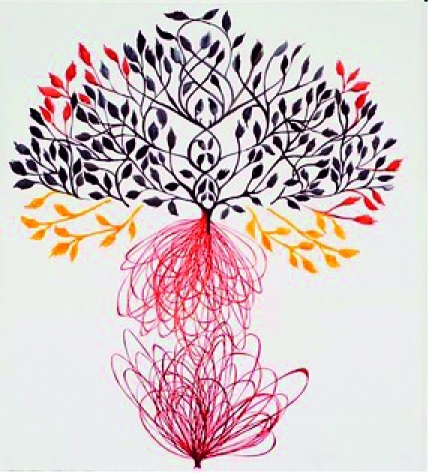

Throughout human evolution, we have been exposed to such complex patterns, and in logical terms only, it seems that we inherently respond positively to similar aesthetic qualities, as shown in images 4 and 5.

Image 4 – ‘Endless Rings’ by Walter Jack

Image 5 – ‘Murals’ by Hanneline Visnes © 2010, The Royal Society of Medicine Louise Lankston, Pearce Cusack, Chris Fremantle, and Chris Isles, Visual art in hospitals: case studies and review of the evidence, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2010 Dec 1; 103(12): 490–499

This is very much an approach taken at IBI, not only when considering healthcare schemes, but across sectors. The Sir Robert Ogden Macmillan Centre adopted this approach through the appointment of a lead artist to support the commitment of Macmillan in providing truly supportive environments. This article’s cover image showcases a poignant example of how art can be integrated within healthcare environments with the use of a comprehensive engagement process. The use of materials suggests a sense of tactility and time, whilst the punctured surface references natural forms and complexity.

Although having only just touched the surface of such a broad and detailed subject, the intention has been to introduce the significance of art within curative environments, and to highlight biophilic design as one of the key principles, that when combined with art can aid in the curative process. With the sheer amount of possibilities art has to offer, its place in a world saturated with visual imagery is becoming greatly necessary. “The poetic image directs and focuses the viewer/ listener/ reader/ occupant’s attention and gives rise to an altered state of consciousness, which evokes an imaginary dimension, an imaginative world”.

Cover image: Sir Robert Ogden Macmillan Centre, Harrogate – photography by Infinite 3D