A “PUF” of Inspiration Towards Net Zero Neighbourhoods

By Kira Hunt

Date

May 2, 2018One cold spring morning in 2013, I was joined by two eager volunteers to lay out the pathways for our new community garden, Prairie Urban Farm (PUF). Located on the University of Alberta’s South Campus in Edmonton, PUF was designed to be a demonstration farm to test sustainable mixed-crop food systems. Little did I know that this volunteer experience would later be important to my work with IBI Group and its research into Net Zero Neighbourhoods, a project that started as a broad investigation of net zero strategies and gradually expanded into an extensive examination of cost-effective first steps for building sustainable communities.

The Nuances of Net Zero

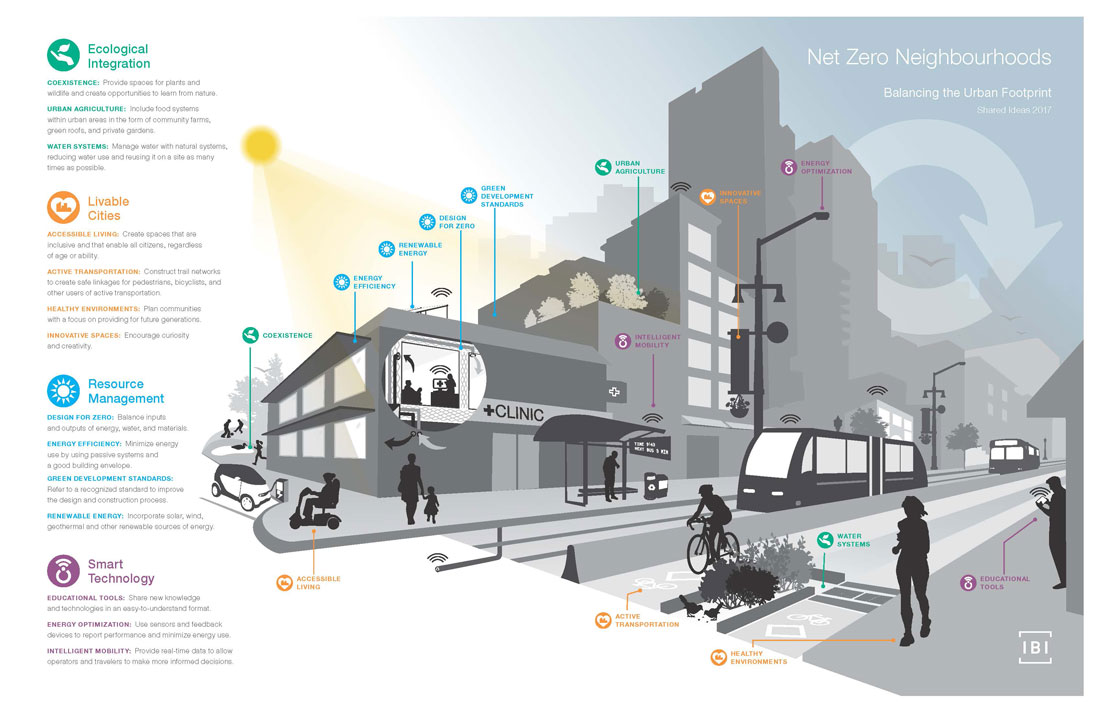

Net zero communities are designed to balance the use and generation of energy, a calculation that is averaged on a yearly basis. The community scale is a practical size for examination: an entire city is just too big to change as a unit, and a single building impacts the lives of only a few users.

Achieving net zero requires efficiency, and consideration of water and material use as energy is required to collect, modify and move resources around. Balancing energy and water use are well-understood concepts; applying net zero thinking to material use is trickier though. If the goal is to generate as much material as we consume, where are those ongoing inputs going to come from?

To Feed a Village

The 100-mile diet? How about the 1-mile diet! Food is a pervasive and persistent material input of communities: growing food close to home just makes sense, reducing long-distance transportation, prolonged refrigeration, and single-use packaging. A community garden can significantly reduce a community’s material inputs, which brings us back to PUF. Organized as a single unit, the garden does not have individual plots; the space is shared, and so is the surplus. It really does take a village…

And it feeds a village too! In just four years, over 200 volunteers have contributed to the space, taking home seedlings and fresh vegetables in return for their labour. Food is also donated to local organizations: some 1000 pounds (450 kilograms) in 2017 alone.

The Circular Economy

PUF is only a small example of the potential for material cycling in our neighbourhoods, but re-integrating food production and daily life – systems that were traditionally linked – will be key to balancing the material inputs and outputs of our communities.

In my work with IBI Group, I have helped design community gardens for two other residential developments. I have watched them build communities that cycle local resources, encourage resource sharing, and forge deeper interconnections.

These ideas are not new, what is new is the need to calculate the costs and benefits of our designs in terms of energy, materials and water flows, and to determine how these designs will impact a community’s long-term sustainability. As nature and landscape professionals, we are uniquely positioned to re-link our human systems with the natural ones surrounding us.

_______

This is an excerpt of a longer article published in Landscape/Paysages Magazine for the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects. Read the full article here.